What is keratoconus? How can it be treated?

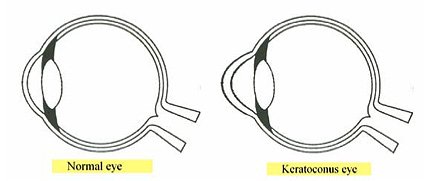

Keratoconus, pronounced KEHR-a-toh-kohn-nus, is a vision disorder that occurs when the normally round, dome-shaped cornea progressively thins, causing a cone-like bulge to develop. Examples of a normal-shaped eye and a dome-shaped keratoconus eye are shown here.

Since the cornea is responsible for refracting most of the light coming into the eye, abnormalities of the cornea can create an associated reduction in visual acuity. The abnormal shape of the keratoconic cornea prevents the light entering the eye from being properly focused on the retina for sharp, clear vision. The bulging or cone-shape protrusion is caused by the normal pressure of the eye pushing out on the thinned areas of the cornea. The changes in the cornea’s natural domed shape often lead to significant distortion and a reduction in vision sharpness (visual acuity). This impairment in vision can severely affect a keratoconus patient’s life by making even simple daily tasks such as driving, watching television, or reading a book, difficult to perform. The actual cause of keratoconus is not yet known, but there have been studies that suggest a genetic link to the disease. The disease typically affects both eyes, but they may not be affected at the same rate.

In the early stages of the disease, keratoconus causes blurring and distortion of vision, along with an increased sensitivity to glare and light. These symptoms usually first appear during your teen years to early 20s. Keratoconus may progress for another 10 to 20 years, with the rate of progression typically slowing during your 40s. As keratoconus progresses, vision often becomes more distorted. Glasses or soft contact lenses may be used to correct the mild nearsightedness and astigmatism that is created in the early stages of keratoconus. As the disease progresses and the cornea continues to thin and change shape, rigid gas permeable (RGP) lenses are often prescribed because glasses and soft contact lenses are no longer adequate to correct your vision. The RGP lenses must be carefully fitted, and frequent checkups and lens changes are often required to continue to achieve good vision. However, over time, the cornea may become scarred and contact lenses may no longer be comfortable to wear on a daily basis or able to adequately correct vision. In severe cases of keratoconus, the last resort is to have a corneal transplant treatment, also known as a penetrating keratoplasty procedure (PKP), due to the development of corneal scarring, corneal thinning, or the inability to wear contact lenses any longer. A corneal transplant procedure involves removing the patient’s cornea and replacing it with healthy corneal tissue from a donor. Most patients will still need to wear glasses or contact lenses for clear vision following a corneal transplant.

In the past, when RGP lenses were no longer effective or became uncomfortable to wear every day, a corneal transplant was the only option for a keratoconus patient. But that has changed. Cross-linking may offer an alternative to restore functional vision and potentially defer the need for a corneal transplant procedure.